WHAT REALLY IS AI??

- jilfadons

- Sep 14, 2024

- 15 min read

FIRSTLY, AI MEANS ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the capability of a digital computer or robot to perform tasks typically associated with human intelligence, such as reasoning, learning, and problem-solving. The term is often linked to the effort of developing systems that mimic human intellectual processes, including understanding meaning, generalizing from data, and learning from past experiences.

Since the 1940s, digital computers have been designed to handle increasingly complex tasks, such as proving mathematical theorems and playing chess with great skill. Despite advances in processing power and memory, no AI system can yet match the full flexibility and adaptability of human intelligence across a wide range of tasks, particularly those requiring common sense or everyday knowledge. However, in specialized areas like medical diagnosis, search engines, voice and handwriting recognition, and chatbots, AI systems have reached expert-level performance. In these narrow applications, AI is already demonstrating its potential.

WHAT IS INTELLIGENCE?

Human behavior, even in its more complex forms, is generally attributed to intelligence, whereas the intricate actions of insects are usually not considered evidence of intelligence. What distinguishes the two? Take the example of the digger wasp, *Sphex ichneumoneus*. When the female wasp returns to her burrow with food, she first places it at the entrance, checks inside for any intruders, and then, if the coast is clear, brings the food inside.

However, the instinctual nature of this behavior becomes clear if the food is moved just a few inches while she’s inside the burrow. Upon emerging, the wasp will repeat the entire process of checking and retrieving the food, no matter how many times the food is displaced. This rigid, repetitive behavior highlights the absence of adaptability, a key trait of intelligence. True intelligence involves the ability to adjust to new situations and challenges, something that is notably missing in the wasp’s behavior.

LEARNING

There are several types of learning in artificial intelligence, with the simplest being trial-and-error learning. For example, a basic chess program designed to solve mate-in-one problems might randomly attempt different moves until it finds the correct solution. Once successful, the program could store this solution along with the specific board position, allowing it to recall the answer if it encounters the same situation again. This straightforward form of learning, called rote learning, involves memorizing individual facts or procedures and is relatively easy to program.

A more complex challenge in AI is achieving generalization, where the system applies knowledge from past experiences to new, similar situations. For instance, a program that learns the past tense of English verbs by memorization alone will only be able to provide the past tense for words it has encountered before, such as producing "jumped" only if it has previously seen "jumped." On the other hand, a program capable of generalization can infer patterns—such as the rule of adding "-ed" to regular verbs ending in a consonant—and thus form the past tense of "jump" even if it hasn't encountered the word before, based on its experience with similar verbs.

Reasoning

Reasoning involves drawing conclusions, or inferences, based on available information. These inferences can be classified as either deductive or inductive.

An example of deductive reasoning is. Fred must be in either the museum or the café. He is not in the café, so he must be in the museum. In this case, the truth of the premises guarantees the truth of the conclusion.

In contrast, inductive reasoning is based on probability rather than certainty. For example: Previous accidents of this type were caused by instrument failure. This accident is similar, so it was likely caused by instrument failure. Here, the truth of the premises supports the conclusion but does not guarantee it. Inductive reasoning is frequently used in science, where data are gathered, and models are developed to explain or predict future outcomes. However, these models are always open to revision if new, conflicting data emerge.

Problem Solving in AI

Problem solving in artificial intelligence is often defined as a systematic search through various possible actions to achieve a specific goal or solution. There are two main types of problem-solving methods: special-purpose and **general-purpose**.

- **Special-purpose methods** are designed specifically for a particular problem and leverage the unique characteristics of that problem. These methods are often highly efficient but not adaptable to other situations.

- **General-purpose methods**, on the other hand, are more flexible and can be applied to a wide range of problems. One common general-purpose technique in AI is **means-end analysis**, which involves incrementally reducing the gap between the current state and the desired goal. The program selects actions from a list of available options—for example, a simple robot might choose between actions like PICKUP, PUTDOWN, MOVEFORWARD, and MOVERIGHT—until it reaches the goal.

AI programs have successfully solved a variety of problems, such as identifying winning strategies in board games, generating mathematical proofs, and manipulating virtual objects in simulated environments. These diverse applications showcase the versatility of AI problem-solving techniques.

METHOD AND GOALS IN AI

**Symbolic vs. Connectionist Approaches in AI**

AI research is shaped by two distinct approaches: the **symbolic** (or "top-down") and the **connectionist** (or "bottom-up") methods. These approaches reflect different philosophies about how to model intelligence.

- The **top-down** or **symbolic** approach aims to replicate intelligence by focusing on cognition independently from the biological structure of the brain. It relies on the manipulation of symbols to represent knowledge and thought processes, making it more abstract. This approach involves creating computer programs that process symbols and apply rules, such as logic or geometric analysis, to solve problems.

- The **bottom-up** or **connectionist** approach, in contrast, seeks to imitate the brain’s biological structure by building **artificial neural networks**. These networks, modeled after the neurons in the human brain, are trained to recognize patterns by adjusting connections between artificial neurons based on experience. This approach emphasizes learning and adaptation over time.

For example, in a system designed to recognize letters of the alphabet:

- A **bottom-up** approach would involve training a neural network by presenting letters one at a time and adjusting the system’s pathways (neural connections) until it learns to recognize each letter correctly.

- A **top-down** approach, however, would involve programming the system to compare the shape of each letter with pre-defined geometric descriptions to identify it.

In essence, the **bottom-up** approach focuses on replicating neural activity, while the **top-down** approach relies on symbolic descriptions and cognitive rules. Both approaches contribute to advancing AI, but they take fundamentally different paths in understanding and building intelligence.

In *The Fundamentals of Learning* (1932), psychologist **Edward Thorndike** from Columbia University proposed that human learning is based on some unknown mechanism within the connections between neurons in the brain. Later, in *The Organization of Behavior* (1949), **Donald Hebb**, a psychologist at McGill University, advanced this idea by suggesting that learning involves the strengthening of specific neural patterns. He theorized that the probability of neuron firing between connected neurons increases when certain patterns are repeatedly activated, a principle now known as **Hebbian learning**.

In 1957, two proponents of the symbolic AI approach, **Allen Newell** of the RAND Corporation and **Herbert Simon** of Carnegie Mellon University, introduced the **physical symbol system hypothesis**. This hypothesis asserts that the manipulation of symbolic structures is sufficient to produce artificial intelligence in a digital computer. Furthermore, they proposed that human intelligence operates through similar symbolic manipulations, highlighting the symbolic or top-down approach as a valid pathway for replicating human cognition in machines.

**Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), Applied AI, and Cognitive Simulation**

AI research pursues one of three primary goals: **artificial general intelligence (AGI)**, **applied AI**, or **cognitive simulation**. Each represents a different approach and ambition within the field.

1. **Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)**, also known as **strong AI**, aims to create machines that can think with a general intellectual capacity indistinguishable from that of humans. AGI seeks to replicate human-like reasoning, problem-solving, and learning across a broad range of tasks. However, progress toward AGI has been inconsistent, and there is debate over whether AGI can be achieved through current techniques, such as large language models, or if an entirely new approach is required. Some researchers even question whether AGI is a worthwhile goal.

2. **Applied AI**, or **advanced information processing**, focuses on creating practical, commercially viable systems. These "smart" systems are designed for specific applications, such as expert systems for medical diagnosis or automated stock-trading platforms. Unlike AGI, applied AI has seen significant success, with numerous real-world applications already in use.

3. **Cognitive simulation** involves using computers to model and test theories about human cognition. For example, cognitive simulation is used to understand how humans recognize faces, recall memories, or make decisions. This approach is a valuable tool in both neuroscience and cognitive psychology, helping researchers explore and validate theories about the workings of the human mind.

Each of these branches of AI research offers unique insights and applications, but they vary in terms of ambition, feasibility, and success.

**AI Technology**

In the early 21st century, advancements in processing power and the availability of large datasets, often referred to as **"big data,"** significantly accelerated the development of artificial intelligence, moving it from specialized research labs into broader commercial and societal applications. **Moore’s law**—the observation that computing power roughly doubled every 18 months—remained a key factor driving this progress.

For perspective, early AI systems like the chatbot **Eliza** could function with a mere 50 kilobytes of data, producing basic conversational responses. In contrast, modern AI models such as **ChatGPT** are trained on vast datasets, with ChatGPT's core language model utilizing around **45 terabytes** of text. This massive increase in both data and processing power has enabled AI to handle more complex tasks, making it far more versatile and impactful in fields such as language processing, healthcare, finance, and beyond.

**Machine Learning**

Machine learning saw a significant advancement in 2006 with the development of **"greedy layer-wise pretraining"**. This technique made it easier to train deep neural networks by training each layer individually before combining them into a complete network. This method paved the way for **deep learning**, a subset of machine learning involving neural networks with four or more layers (including input and output layers).

Deep learning networks are capable of **unsupervised learning**, meaning they can identify and extract features from data without explicit guidance. This capability allows these networks to discover patterns and make sense of complex data independently.

One notable achievement of deep learning is in **image classification**, where specialized neural networks known as **convolutional neural networks (CNNs)** are used. CNNs are designed to recognize and classify features in images by comparing input images with those in their training datasets. For instance, CNNs can identify objects such as cats or apples based on learned features.

An example of a successful deep learning network is **PReLU-net**, developed by Kaiming He and his team at Microsoft Research. This network has demonstrated image classification performance that surpasses even human ability, showcasing the impressive capabilities of deep learning in practical applications.

**Autonomous Vehicles**

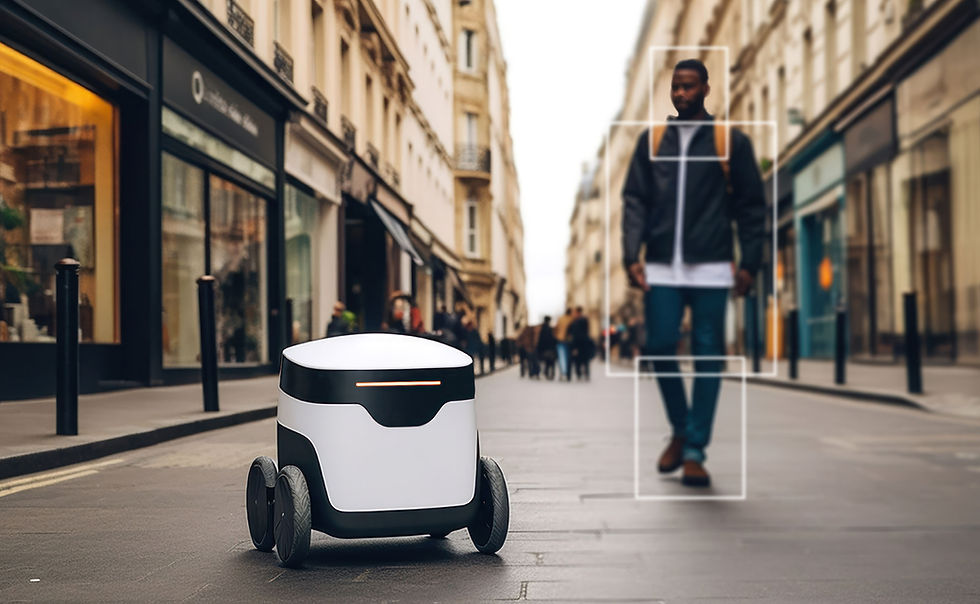

Machine learning and AI are critical to the development of autonomous vehicles, where they are used to analyze complex data such as the movement of other vehicles and road signs. These technologies help refine algorithms that enable vehicles to make decisions without needing explicit instructions for every possible scenario.

To ensure the safety and effectiveness of autonomous vehicles, artificial simulations are created for testing. **Black-box testing** is used in these simulations, contrasting with **white-box validation**. White-box testing involves knowing the internal structure of the system being tested, allowing for thorough verification. In black-box testing, the system’s internal workings are unknown to the tester, who focuses on the system's external behavior and aims to identify potential weaknesses. This approach is crucial for validating the robustness of autonomous vehicle systems against various challenges.

As of 2024, fully autonomous vehicles are not yet available for consumer purchase. Several obstacles remain, such as the need for comprehensive maps of nearly four million miles of U.S. public roads. Additionally, vehicles equipped with self-driving features, like those from Tesla, have faced safety concerns, including incidents involving oncoming traffic and collisions with metal posts. Current AI systems lack the “common sense” needed to handle complex interactions with other drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians, which is essential for ensuring safety and preventing accidents.

**Waymo**, Google's self-driving car project (which began in 2009), achieved a significant milestone in October 2015 by completing its first fully driverless trip with a passenger. The technology has been extensively tested, accumulating one billion miles in simulations and two million miles on real roads. Waymo operates a fleet of fully electric vehicles in San Francisco and Phoenix, offering ride-hailing services similar to Uber or Lyft, with no need for human control over the steering wheel, gas pedal, or brake pedal.

Despite Waymo’s early success and a peak valuation of $175 billion in November 2019, its value dropped to $30 billion by 2020. The technology is under investigation by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) due to multiple reports of traffic violations, including incidents of driving on the wrong side of the road and hitting a cyclist. These issues highlight ongoing challenges in perfecting autonomous vehicle technology.

**Virtual Assistants**

Virtual assistants (VAs) perform a wide range of tasks, such as scheduling, making and receiving calls, and providing navigation assistance. These assistants rely on large datasets and learn from user interactions to enhance their ability to predict user needs and behaviors. Popular virtual assistants include **Amazon Alexa**, **Google Assistant**, and **Apple’s Siri**. Unlike basic chatbots or conversational agents, VAs offer a more personalized experience by adapting to individual users' behaviors and learning from their interactions over time.

The development of human-machine communication began in the 1960s with **Eliza**, a pioneering chatbot. In the early 1970s, **PARRY**, designed by psychiatrist Kenneth Colby, aimed to simulate a conversation with someone with paranoid schizophrenia. In 1994, **Simon**, developed by IBM, introduced features like a touchscreen, email, and fax capability, marking a significant step toward modern smartphones. Although Simon was not a virtual assistant, it played a crucial role in paving the way for future developments.

The modern era of virtual assistants began with **Siri**, introduced in February 2010 for iOS on the iPhone 4S. Siri was the first VA to be downloadable to a smartphone, setting a precedent for future assistants.

Virtual assistants process human speech using **automatic speech recognition (ASR)** systems. They break down speech into phonemes, analyze the tone and other vocal features, and use this information to recognize the user. Over time, VAs have become increasingly sophisticated through machine learning, drawing on extensive datasets of words and phrases. They also utilize the internet to provide answers to user queries, such as checking the weather forecast.

This ongoing advancement in virtual assistant technology continues to enhance their functionality and integration into everyday life.

**Risks of AI**

The rise of artificial intelligence brings several ethical and socioeconomic risks that need to be addressed:

1. **Job Displacement**: Automation of tasks, particularly in fields like marketing and healthcare, may lead to significant job losses. While AI could create new job opportunities, these positions often require more advanced technical skills than the roles being replaced. This shift could exacerbate inequality and make it challenging for workers to transition to new roles.

2. **Bias**: AI systems can perpetuate and even amplify human biases. For example, predictive policing algorithms used by U.S. police departments may rely on historical arrest data, which can be biased against marginalized communities. This can lead to over-policing in certain areas, further reinforcing existing biases. As AI systems reflect the biases present in their training data, addressing these biases requires ongoing effort and careful design.

3. **Privacy Concerns**: AI often involves the collection and analysis of large datasets, raising concerns about data security and privacy. There is a risk that sensitive information could be accessed by unauthorized individuals or organizations. Generative AI technologies, which can create convincing fake images and profiles, add another layer of risk, including the potential for misuse in surveillance and tracking of individuals in public spaces.

4. **Abuse and Misinformation**: The misuse of AI for creating non-consensual deepfakes and other forms of digital abuse is a growing concern. For instance, in January 2024, singer Taylor Swift became a high-profile target of sexually explicit deepfakes circulated on social media. This case highlighted the broader issue of AI-enabled online abuse, bringing increased attention to the need for robust policies to protect individuals from such harm.

Experts advocate for the development of policies and practices that maximize the benefits of AI while minimizing its risks. Ensuring responsible use of AI requires a balanced approach that considers ethical implications, safeguards privacy, and addresses biases effectively.

**AI and Copyright Issues**

AI has raised significant concerns related to copyright law and policy:

1. **Use of Copyrighted Works**: In 2023, the U.S. Copyright Office initiated an investigation into how AI systems use copyrighted materials to generate new content. This scrutiny came in response to a surge in copyright-related lawsuits. For example, Stability AI faced legal action from Getty Images for allegedly using unlicensed images to create new content. Getty Images also introduced its own AI feature to address issues arising from services offering "stolen imagery."

2. **AI-Created Content and Copyright**: There are ongoing debates about whether content generated by AI should be eligible for copyright protection. Currently, AI-generated works cannot be copyrighted, but the discussion continues regarding the potential for legal changes in this area.

**Ethical and Labor Concerns**

AI's rise has also highlighted ethical issues related to labor:

1. **Exploited Workers**: Despite claims of automation and minimal human involvement, many AI technologies rely on low-wage labor, often from developing countries. For instance, a Time magazine investigation revealed that OpenAI employed Kenyan workers to sift through text snippets to remove harmful content from ChatGPT. These workers, paid less than $2 an hour, faced traumatic experiences, leading to the project's cancellation in February 2022.

2. **Outsourced Labor for Automation**: Amazon's promotion of its **Amazon Go** stores as fully automated faced scrutiny when it was discovered that the technology was supported by outsourced labor from India. Over a thousand workers acted as “remote cashiers,” challenging the notion of full automation and sparking criticism and jokes about the real nature of AI in this context.

These issues underscore the need for a comprehensive approach to AI development that addresses legal, ethical, and labor concerns to ensure that technological advancements do not come at the expense of human rights and fair practices.

RECENT REPORTS - AS AT 11:15 SEPTEMBER 11 2024

**Quantum Computers**

A quantum computer leverages the principles of quantum mechanics to potentially revolutionize computing power. Richard Feynman, in 1959, first proposed the idea that as electronic components shrink to microscopic scales, quantum effects could be harnessed to create more powerful computing devices. This concept is rooted in the phenomenon of **superposition**, where quantum objects can exist in multiple states simultaneously until measured.

In quantum mechanics, a photon passing through a double-slit apparatus creates an interference pattern, illustrating superposition. The photon effectively explores all possible paths, resulting in a wavelike pattern. When a measurement is made to determine which slit the photon passed through, this interference pattern disappears, and the photon is forced into a definite state. Quantum systems operate in a superposition of all possible states until a measurement collapses them into a single outcome.

This principle translates to quantum computing in the form of **quantum bits** or **qubits**. Unlike traditional digital computers that use binary digits (bits) which can be either 0 or 1, qubits can exist in a superposition of both 0 and 1 simultaneously. For example, while a 4-bit register in a digital computer can represent one of 16 possible values (2^4), a 4-qubit register can represent all 16 values at once.

This ability to perform parallel computations means that quantum computers have the potential to process vastly more data simultaneously than classical computers. For instance, a 30-qubit quantum computer could theoretically match the performance of the fastest classical supercomputers, capable of executing up to 10 trillion floating-point operations per second (TFLOPS).

Quantum computing is still in its early stages, but its potential to solve complex problems that are currently intractable for classical computers makes it a highly promising field in the quest for advanced computational capabilities.

**Early Quantum Computing Milestones**

In 1998, Isaac Chuang from Los Alamos National Laboratory, Neil Gershenfeld from MIT, and Mark Kubinec from the University of California, Berkeley, achieved a significant breakthrough in quantum computing by creating the first functional quantum computer with 2 qubits. This early quantum computer was capable of being loaded with data and providing an output, marking a foundational step in demonstrating quantum computation principles.

Their approach involved using chloroform molecules (CHCl₃) dissolved in water at room temperature. By applying a magnetic field to align the spins of the carbon and hydrogen nuclei within the chloroform, they created a system where the spin states could represent qubits. Specifically, they used carbon-13, an isotope with magnetic properties, as ordinary carbon does not have a magnetic spin. The hydrogen nuclei and carbon-13 nuclei were collectively treated as a 2-qubit system. The system's qubits could be manipulated using radio frequency pulses to flip the spin states, creating superpositions of parallel and antiparallel states. The team then applied additional pulses to execute a simple quantum algorithm and examine the final state of the system.

In March 2000, Emanuel Knill, Raymond Laflamme, Rudy Martinez from Los Alamos, and Ching-Hua Tseng from MIT advanced the field by creating a 7-qubit quantum computer using trans-crotonic acid. Despite these achievements, researchers are cautious about scaling magnetic techniques beyond 10 to 15 qubits due to challenges with maintaining coherence among the nuclei, which becomes increasingly difficult as the number of qubits grows.

These early experiments demonstrated the feasibility of quantum computation and laid the groundwork for further research into more complex quantum systems and algorithms.

**Advancements in Quantum Computing**

Just one week before the announcement of the 7-qubit quantum computer, David Wineland and colleagues at the U.S. National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) unveiled their own breakthrough: a 4-qubit quantum computer. This system used an electromagnetic "trap" to confine and entangle four ionized beryllium atoms. By cooling the ions to nearly absolute zero with a laser and synchronizing their spin states, the team was able to entangle the particles, creating a superposition of both spin-up and spin-down states across all four ions. This experiment demonstrated fundamental quantum computing principles, though scaling up the technology for practical use remains a challenge.

Another promising avenue in quantum computing involves semiconductor technology. In this approach, free electrons act as qubits and are confined within tiny regions called quantum dots. These quantum dots, each housing a single electron in one of two spin states (0 or 1), are integrated into semiconductor devices. Although quantum dots are susceptible to decoherence, they leverage established solid-state technologies and the potential for scaling with integrated circuits. Large arrays of quantum dots can be fabricated on a single silicon chip. This chip operates in an external magnetic field to control electron spin states, with neighboring electrons weakly entangled through quantum mechanical effects.

An array of wire electrodes addresses individual quantum dots, allowing for the execution of algorithms and extraction of results. To mitigate decoherence from environmental factors, these systems must operate at temperatures close to absolute zero. However, they hold promise for incorporating a large number of qubits, potentially advancing quantum computing capabilities significantly.

Comments